Right Concentration

This section is in early stages of progress.

Jhāna: Mundane and Supra-mundane Right Concentration

Right concentration is often spoken of as a single factor of the path, yet the discourses clearly distinguish two modes in which it operates. These are commonly called mundane and supra-mundane Right Concentration. The difference between them is not merely a matter of depth or intensity, but a difference in how unification of mind comes about.

Understanding this distinction helps clarify why deep absorption alone does not constitute liberation, and why liberation necessarily includes a kind of concentration that is not fabricated by effort.

Mundane Right Concentration

Mundane Right Concentration belongs to the domain of training. It is intentionally developed and intentionally maintained. Attention is gathered, directed, and held to a chosen object. Through repeated application and refinement, the mind becomes unified.

Here, one pointedness is constructed. Intention plays an active role. Attention is repeatedly brought back, protected from distraction, and stabilized. Factors such as applied and sustained attention, joy, pleasure, and composure are deliberately supported. Even when effort becomes subtle, it is still present as maintenance.

This kind of concentration is wholesome and powerful. It suppresses unwholesome states and provides clarity, stability, and ease. It is indispensable for calming the mind and preparing it for insight. However, it remains conditioned. It depends on doing. When the supporting conditions are withdrawn, the concentration fades.

For this reason, mundane Right Concentration is still part of becoming. It refines experience, but it does not end appropriation. There is still an implicit sense of holding, sustaining, or returning. Even when the sense of self is faint, fabrication is still operating.

Supra-mundane Right Concentration

Supra-mundane Right Concentration arises in a fundamentally different way. It is not produced by gathering attention, nor by narrowing the field of experience. Instead, it appears when clinging ceases at the level of the path.

Here, one pointedness is not made. It is the result of conditions.

Attention is unified because nothing is pulling it apart. The forces that normally scatter the mind, craving, aversion, restlessness, and confusion, are absent. There is no need to suppress them, because they are not operating. As a result, consciousness stands unified without effort.

This concentration is inseparable from Right View. It is explicitly described as concentration supported by the other factors of the noble path. Because understanding is present, there is no leaning toward experience, no attempt to hold or arrange it, no subtle claiming of it as mine.

The mind is composed, but not through control. It is steady, but not through holding. It is one pointed, but not narrowed. Knowing is clear and unobstructed, yet free from intentional shaping.

Fabrication and Freedom

The key distinction between these two lies in fabrication.

In mundane concentration, unification depends on fabrication. Intention organizes experience so that consciousness remains collected. This fabrication is wholesome and skillful, but it is still fabrication.

In supra-mundane concentration, unification remains when fabrication stops. Experience continues, consciousness continues, knowing continues. What has ceased is the extra movement that tries to manage, sustain, or appropriate experience.

This is why supra-mundane concentration cannot be practiced in the usual sense. It occurs when conditions are fulfilled, particularly when clinging is abandoned through clear seeing. It is not entered into, but rather uncovered.

Why the Distinction Matters

Without this distinction, it is easy to mistake refined states of absorption for liberation. A mind can be extremely unified and still be dependent on doing. As long as concentration must be maintained, it remains conditioned.

At the same time, supra-mundane concentration does not negate the value of mundane concentration. The latter prepares the ground. It stabilizes the mind so that the mechanisms of clinging can be seen clearly. Without this stability, the ending of fabrication would not be discernible.

Right Concentration, then, is not simply about stillness. It is about how stillness comes to be. When stillness is fabricated, it is mundane. When stillness remains because clinging has ceased, it is supra-mundane.

This difference marks the boundary between training and realization, between composure that is made and composure that is free.

Jhāna: Two Pathways to Stillness

In the Gradual Training, the Tathāgata spoke of two paths: the mundane and the supra-mundane. The mundane path is the skillful fabrication of karma to address the afflictions. The supra-mundane path is the way of the noble ones, a mind that, having seen the futility and dissatisfaction in fabrication, inclines toward letting go.

On the mundane path, we practice Right Concentration through skillful fabrication: the deliberate refinement of attention, perception, and feeling to cultivate the deep absorptions, the jhānas. Here, we are absorbed in our fabrications.

By contrast, the supra-mundane path is the gradual realization of the cessation of karma, the letting go of conceiving (maññanā). It is the progressive stilling of the mental fabrications that construct experience: such as “I exist in this body,” “I see through these eyes,” or “I dwell upon this earth.” This is how one dismantles the construction of the experiential world itself.

This is not absorption into form, but a dwelling free from conceiving, free from the thought, “I exist.”

The mundane path brings bliss born of seclusion; supra-mundane bliss is from letting go.

The stilling of all formations, the relinquishment of all acquisitions, the destruction of craving, dispassion, cessation, Nibbāna.

SN36.11

Fabricated Bliss: The Skillful Construction of Jhāna

The mundane jhānas (lokiya-jhāna) are wholesome formations. They arise when the mind, secluded from the hindrances, becomes unified and suffused with rapture and pleasure born of concentration.

Quite secluded from sensual pleasures, secluded from unwholesome states, a disciple enters and dwells in the first jhāna, which is accompanied by applied and sustained attention, with rapture and pleasure born of seclusion.

DN2

Here, perception is intentionally shaped. Attention is directed to a single object, such as the breath or the four elements, while pleasant feeling is cultivated and coarse thought subsides. With each successive jhāna, perception refines until the mind becomes silent, balanced, and steady.

Characteristics of Fabricated Jhāna:

-

It depends on effort and perception.

-

It is experienced as “I am calm” or “I am dwelling in peace.”

-

It fades when attention wavers.

-

It remains within the domain of the Five Aggregates.

Though conceiving is quieted, the subtle sense of “I experience this stillness” persists. Thus, the Tathāgata called it a temporary liberation of mind (tadaṅga vimutti).

Un-fabricated Jhāna: The Joy of Letting Go

At a more mature stage of practice, we begin to see that even refined jhāna is a fabrication, that bliss and equanimity arise and pass away due to conditions. Seeing this clearly, the mind no longer clings even to calm and happiness, recognizing them as ultimately unsatisfying.

With supra-mundane wisdom, Right View, the mind turns away from constructing and toward understanding how construction itself occurs, inclining toward relinquishment rather than creation.

As practice deepens, attention moves from working with perception to working directly with consciousness, tracing the chain of dependent origination to subtler levels. Here, one learns to let go of conceiving itself, the mental creation of “I am this” or “I am in this.”

He does not conceive earth as self, he does not conceive self as possessing earth, he does not conceive self in earth, he does not conceive earth in self.

When he does not conceive anything in any way, he does not cling to anything in the world. When he does not cling, he is not agitated. When he is not agitated, he personally attains Nibbāna.

MN140

Here, bliss is not fabricated by attention or effort. It arises naturally when the burden of fabrication falls away.

Characteristics of Un-fabricated Jhāna:

-

It is effortless, not made, and not sustained.

-

There is no sense of “I am experiencing this.”

-

It is stable in all conditions.

-

It does not depend on creating perceptions or feelings.

-

It is the joy of release (vimutti-sukha).

The Tathāgata called this supra-mundane jhāna (lokuttara-jhāna), the same stillness as the mundane, but transformed by wisdom. The insight “This too is not mine, not I, not myself” penetrates even the calm itself.

There is, disciples, an unborn, unbecome, unmade, unconditioned. If there were not this unborn, unbecome, unmade, unconditioned, there would be no escape from the born, the made, the conditioned.

But since there is this unborn, unbecome, unmade, unconditioned, therefore an escape is discerned.

UD8.3

Only the supra mundane Jhāna leads to the end of fabrication, the cessation of conceiving. The mind no longer constructs “a state” in which to dwell. Nibbana is not created; it is revealed when creating stops.

Right Concentration: Mundane and Supra-mundane

Right Concentration can function in two distinct ways, depending on whether it is still serving the maintenance of refined experience or whether it is aligned with release. The difference is not in the external form of jhāna, but in how it is understood and what it is used for.

Mundane Right Concentration

Mundane Right Concentration refers to jhāna developed as a wholesome, stabilizing, and purifying state, but not yet fully integrated with liberating insight.

Here, the mind becomes secluded from sensuality and unwholesome states. Attention gathers, perception refines, and joy, tranquility, and equanimity arise in dependence on unification. The mind is bright, steady, and malleable.

However, at this level, concentration is still implicitly taken as something valuable in itself. There can remain a subtle sense of attainment, continuity, or reliance on the refined state. Even when coarse self-view has weakened, refined experience may still be quietly appropriated as “my calm,” “my clarity,” or “my absorption.”

This does not mean craving is gross or active. It is often very subtle, expressed as a preference for the stability, purity, or pleasure of collected states. Because of this, mundane concentration, though powerful, does not by itself bring about irreversible release.

Yet it is indispensable. It purifies perception, stills the mind, and creates the conditions in which insight can arise without distortion.

The Turning Point

The shift from mundane to supra-mundane Right Concentration does not occur by changing the jhāna factors. It occurs when the same collectedness is no longer used to maintain experience but to see through it.

This turning point is marked by a clear understanding that even the most refined concentration is conditioned, impermanent, and incapable of providing lasting satisfaction. The mind no longer inclines toward preserving the state, improving it, or identifying with it.

At this point, concentration stops serving refinement and begins serving release.

Supra-mundane Right Concentration

Supra-mundane Right Concentration is concentration functioning within the Noble Eightfold Path, supported by Right View that sees the Four Noble Truths directly.

Here, jhāna is not entered to dwell in pleasure, calm, or purity, but because the mind naturally gathers when craving is absent. Collectedness is a byproduct of relinquishment, not an achievement.

Perception remains unified, but it is no longer appropriated. Feeling is present, but it is not measured against satisfaction. Attention does not circle experience or try to preserve it. Because ownership has weakened at the level of view, concentration no longer feeds self-making.

In this mode, even the refined states of jhāna are known clearly as conditioned processes. Their arising, persistence, and cessation are seen without disturbance. This is what MN 111 points to: phenomena within jhāna are discerned as they actually are, while the mind remains unagitated.

Supra-mundane Right Concentration is therefore not a different jhāna but a different relationship to jhāna. It is concentration that cooperates with insight rather than obscuring it.

The Essential Difference

The essential difference can be summarized simply:

Mundane Right Concentration purifies experience. Supra-mundane Right Concentration dismantles appropriation of experience.

In mundane concentration, perception becomes refined. In supra-mundane concentration, the conceit “I am the one experiencing” is no longer reinforced.

In mundane concentration, attention is unified. In supra-mundane concentration, even that unification is known as not mine.

Because of this, supra-mundane Right Concentration supports the irreversible weakening of the fetters. It does not hold the mind in a refined state; it allows the mind to see why no state can be held.

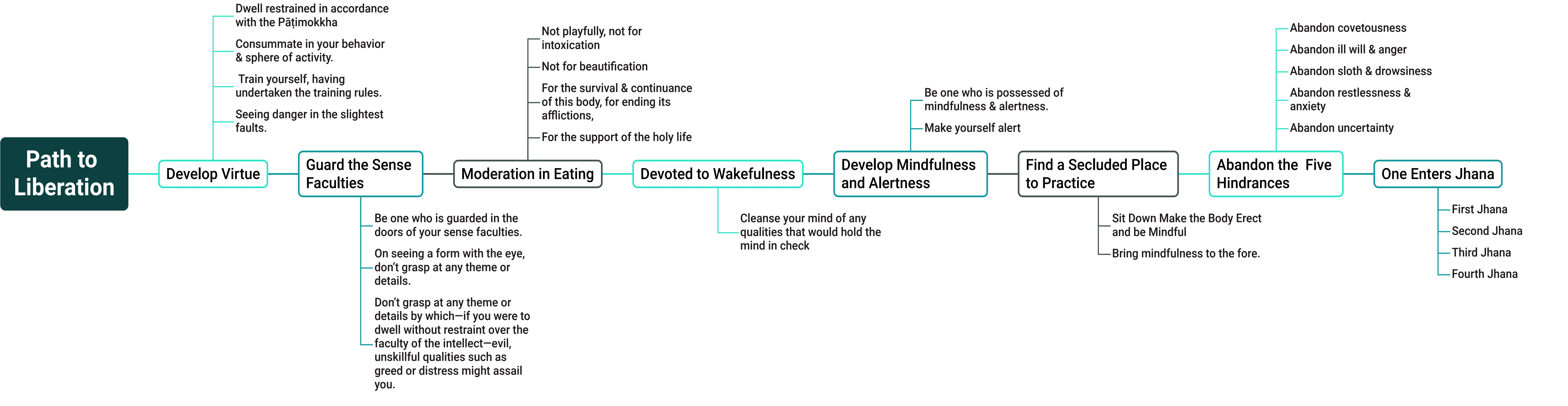

Right Concentration: Overview of the Practice

In the previous stage of the Gradual Training, we purified the mind of the Five Hindrances through developing and balancing the Seven Factors of Enlightenment. With the mind thus clear and pliant, we developed the ability to abide in Jhāna.

In this next stage, our task is to master the Four Jhānas. This means learning to enter, dwell in, sustain, emerge from, and reflect upon each of the four absorptions with skill and knowing.

The aim is Jhāna Mastery, to make the four Jhānas our steady dwelling place rather than an occasional attainment. Through training, the mind becomes stable, obedient, and ready to serve wisdom.

We cultivate five kinds of mastery:

-

The ability to direct the mind toward a Jhāna at will.

-

The ability to enter it at will.

-

The ability to remain in it for as long as one wishes.

-

The ability to emerge from it at will.

-

The ability to review it with clear knowing.

Through these five skills, Jhāna becomes a wieldy abiding, serene, steady, and responsive to intention. From this foundation, we progress to the formless attainments, refining concentration beyond form and cultivating the most subtle perceptions.

The goal in this stage of the training is the development of Imperturbability and Purification of Mind, a mind utterly steady, free from disturbance, and perfectly fit for insight. Such a mind becomes the flawless instrument for the next stage of the path: knowledge and vision of things as they really are.

Jhāna: Overview of Supramundane Jhāna

In the Gradual Training, the development of Jhāna marks a profound turning point, not merely a change in what is experienced, but a transformation in the very mode of experience.

Often misunderstood as a trance or a temporary meditative state, Jhāna in the Tathagata's teachings represents something far more radical: a shift in the dwelling place of consciousness, from the physical, sensory body to a luminous, mind-constructed form (manomaya kāya).

The First Step: Seclusion

The entry into Jhāna does not begin with pleasure or deep concentration, but with seclusion, the deliberate withdrawal from sensory engagement and unwholesome states of mind.

Quite secluded from sensual pleasures, secluded from unwholesome states...

DN2

This seclusion is not only ethical or mental, but sensory: a complete stepping back from the five physical senses.

Having gone beyond the body, and abandoning the perception of the body, and with the cessation of sense impressions... one touches with the body that which is neither seen nor heard nor sensed nor cognized.

MN140

At this stage, perception no longer depends on sights, sounds, smells, tastes, or tactile sensations. Awareness becomes fully internalized, resting in a purely mental field, the domain of mind rather than matter.

Jhāna as a Dwelling (Vihāra), Not a State

The Tathāgata consistently described Jhāna using the verb "viharati", “to dwell” or “to abide.” This choice of language reveals an important truth: Jhāna is not a fleeting state but a new mode of abiding, a reorientation of being itself.

One no longer operates within the boundaries of the physical body or the five senses, but from an inward, luminous stability of perception. In modern terms, Jhāna is not a “peak experience,” but a new dwelling of consciousness, a different way of being in the world.

Right Concentration: The Luminous Ground of Experience

Right Concentration (sammā samādhi) is therefore not the temporary suppression of distraction, but the abandoning of the sensory world and the reconstruction of perception and conciousness upon a luminous, volitional ground.

In this sense, Jhāna is not an escape from experience but a reconfiguration of how experience itself is known, a new way of dwelling, acting, and seeing.

From this dwelling, the path of awakening naturally unfolds. With the clarity of the mind-made body, one sees directly that even this luminous form, serene and radiant as it is, is also conditioned and impermanent.

To abide in Jhāna is, in effect, to dwell within one of the thirty-one realms of existence (loka-dhātu) as experienced here and now through the mind. Each Jhāna corresponds to a specific heavenly plane within the Form Realm (Rūpa-loka), where beings are sustained not by coarse physical contact but by the subtle nourishment of mental joy and equanimity.

When the mind abides in the first Jhāna, it partakes in the same mode of consciousness as the deities of the Brahma World, radiant, serene, and secluded from sensuality. As concentration deepens through the higher Jhānas, one ascends through successively purer realms, each more refined and tranquil than the last.

Yet even these luminous abidings, lofty and peaceful as they are, remain within the conditioned cosmos, part of the fabric of becoming. The wise therefore use Jhāna not as an end in itself, but as a dwelling of clarity and steadiness from which to see that even the Brahma realms are impermanent, and that liberation lies beyond all realms, in the cessation of becoming itself.

Right Concentration: Reframing Jhāna

In many contemporary interpretations, Jhāna is portrayed as a temporary altered state, a trance, like absorption into which the practitioner falls. However, in the Tathagata's teachings, Jhāna is consistently described not as a fleeting experience, but as a "vihāra", a dwelling, an abiding, or a new base of operation. It represents a profound shift in the very structure of perception and embodiment.

The Tathagata repeatedly states that one enters and "dwells" in the first jhāna... the second... the third... the fourth" (DN 2, Sāmaññaphala Sutta). The Pāli term viharati indicates residing or abiding. Thus, Jhāna is not something one touches and leaves behind, but a new, sustained mode of being.

In the same discourse (DN 2), following the fourth Jhāna, the practitioner is said to produce a mind-made body (manomaya kāya):

He produces from this body another body, having form, mind-made, complete in all its limbs and parts, not lacking any faculties.

DN2

This marks a crucial transformation. We are no longer bound to the physical body. Perception, intention, and clarity are restructured around a luminous, volitionally sustained form. This body is vivid, complete, and entirely functional.

Luminosity and Awareness: Not Trance

Unlike some modern views which frame Jhāna as an unconscious or trance-like state, the Suttas emphasize mindfulness, discernment, and clarity. For example, in MN 111 (Anupada Sutta), Sāriputta is said to maintain full awareness and reflective insight while progressing through the jhānas:

He understood: 'So this is the first jhāna... this is the second... third... fourth.'

MN111

This level of detailed awareness would be impossible in a state of mental dullness or unconsciousness. Jhāna is luminous and alert.

A New Basis for Practice and Insight

In MN 66 (Laṭukikopama Sutta), the Tathagata compares one who has let go of the physical body to a bird that carries only its wings. The mind-made body is a light, unburdened mode of being, allowing refined perception and further insight:

Just as a bird, wherever it flies, flies with its wings as its only burden...

MN66

Here, the mind-made form becomes the new container for abiding and inquiry.

Thus, Right Concentration (sammā samādhi) is not merely an attainment, but a rebirth into a new perceptual structure. It is the creation and habitation of a luminous, volitionally constructed, mind-made body, which then becomes the platform for deep insight into impermanence, suffering, and not-self.

This understanding of Jhāna, offers a radically more stable and transformative vision of Jhāna: not as escape, but as re-establishment of perception on new, purified ground.

Right Concentration and the Purification of Perception

In the development of Right Concentration, the Disciple withdraws from the physical senses and turns inward to the mind. This withdrawal is not a suppression but a seclusion from coarse sensory input, allowing awareness to center on subtler aspects of experience: feeling (vedanā), perception (saññā), mental formations (saṃkhāra), and consciousness (viññāṇa).

Purification Happens in the Mind

Purification takes place not at the level of the sense consciousness, but in the mind. Eye-consciousness arises when the eye meets a form, but how one perceives and reacts to that experience is determined by the mind. The raw sensory data merely initiates a chain of mental events: perception, conceptualization, and reactivity. Thus, perception is not a feature of the eye, but a mental process that can be trained and purified.

The Role of Perception in Insight

Understanding this distinction is crucial. The six types of consciousness are bare awareness functions and do not by themselves produce recognition. Perception is what identifies and labels: “that is a tree,” “that is a person.” Since perception is mental, its purification requires the practice of cittānupassanā, observing the mind with the mind.

Although all four satipaṭṭhānas support this path, cittānupassanā holds a central role when the goal is purifying perception. Right Concentration thus depends on a purified mind. The Disciple withdraws from attachment to physical input, guards the sense doors, and unifies the mind, a hallmark of jhāna.

Jhānic Perception of Body and Feeling

Once the mind is concentrated, the meditator can return to observing body and feeling, but in a transformed way. The body is no longer experienced through the coarse senses but as a subtle field of perception, as described in MN 39: “He drenches, steeps, fills, and pervades this very body with rapture and pleasure.”

Feelings become purified and more clearly observed in their arising, nature, and impermanence. Though feelings may be triggered by physical contact, they are mental events conditioned by both contact and past kamma. Vedanānupassanā enables the meditator to stay with feeling as feeling, without proliferating into craving and clinging.

In early practice, the role of vedanānupassanā is not full purification but the containment of reactivity. By staying present with bare feeling, the meditator cuts the cycle of proliferation before it matures into suffering.

Similarly, in the early stages of kāyānupassanā, the aim is not deep insight, but stable awareness: not identifying with the body, not reacting to sensation, and creating the ground for deeper purification.

Unification Around a Perception

Jhāna is unification around a perception. In the first jhāna, this might be the breath or a wholesome theme, stabilized by vitakka and vicāra. In the second jhāna, perception unifies around internal bliss. As concentration deepens, each level involves abandoning one perception and cultivating a subtler one. MN 111 describes how Ven. Sāriputta knew and released each perception:

Perceptions in jhāna are mental, not sensory. Even the perception of form remains in the rūpa-jhānas but is refined and internal. MN 43 confirms this:

This refined body is not the gross physical body, but a unified field of internal sensation, sometimes called a light body or elemental body.

Dwelling in the Body During Concentration

To "dwell in the body" during jhāna is to remain mindful of an internal, unified field of form. MN 119 describes the body being pervaded with bliss, like bath powder kneaded with water. The coarse body drops away, replaced by this refined perception.

The Mental Nature of Perception

In the jhānas, all perception is mental. The five senses fall silent through non-attention, not suppression. What remains are perceptions like bliss, equanimity, space, or light, fabricated through attention and mental training. This is not mere concentration but purification of perception.

In ordinary life, the mind habitually overlays raw sense data with concepts, reactions, and stories, resulting in delusion. SN 35.232 outlines this causal chain: contact leads to feeling, craving, perception, proliferation, and mental obsession.

Conscious Fabrication of Wholesome Perceptions

Jhāna training is a deliberate act of fabricating wholesome perceptions. The mind withdraws from the sensory flood and sustains a perception like breath or loving-kindness.

This is not self-deception. The Tathagata taught that volitional fabrication is a tool of liberation.

These tools, once used for delusion, are repurposed for liberation. They are known, not clung to, and eventually relinquished.

From Fabricated to Unfabricated

Even wholesome perceptions are abandoned. MN 106 describes moving beyond the perception of form, resistance, and diversity to the base of nothingness, knowing.

So we transition from deluded perception, to skillful fabrication, to unfabricated awareness. This is the arc of the Dhamma path.

The Perception of the Breath in Jhāna

In jhāna, the physical breath is no longer perceived. What remains is:

-

Mental perception of breath (ajjhatta saññā),

-

Feeling-tone of pīti and sukha,

-

Subtle sense of continuity.

The breath becomes a mental perception, shaped by attention and feeling.

All Perception Is Internal

The Tathagata consistently taught that what we call "outside" is known only through the six sense bases. SN 35.23 states:

Thus, all objects, "external" or "internal", are experienced as mental perceptions.

Why Use Inner Perceptions?

The difference lies in reactivity. Perceptions of the outside world often involve clinging and identity. Jhāna uses neutral, skillful perceptions that support unification and calm. MN 121 describes a progression from coarse to subtle perceptions: village → wilderness → earth → space → nothingness.

Applying Insight to All Perception

Eventually, all perceptions are seen as conditioned, impermanent, and not-self. MN 106 affirms:

The trained mind sees all perception as fabrication. Liberation lies beyond even the most refined perceptions. Right Concentration thus culminates in the insight that frees the mind from all grasping.

Vision and Perception in Jhāna: Mind-Based Seeing

Advanced practitioners often report a seeming paradox: in deep jhāna, they feel disconnected from the physical senses, yet they continue to "see" with clarity. Is this a contradiction? According to the early Buddhist texts, this is not only consistent—it is a mark of success in concentration. The apparent visual field persists, but perception no longer depends on the physical senses. This article explores the sutta basis for this insight and how perception in jhāna operates entirely through the mind.

The Inactivity of the Five Senses

Entering jhāna requires full seclusion from the five physical sense faculties. As the Buddha teaches in MN 140 – Dhātuvibhaṇga Sutta:

Having gone beyond the body, and abandoning the perception of the body, and with the cessation of sense impressions... one touches with the body that which is neither seen nor heard nor sensed nor cognized.

MN140

Here, "cessation of sense impressions" (phassa) means that the eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and body no longer generate new contact with external objects. However, this does not mean perception ceases altogether.

In MN 43 – Mahāvedalla Sutta, the distinction is made clear:

What is the faculty of the eye? That which makes seeing possible. But the mind discerns the nature of those objects.

MN43

This means the mind is the ultimate interpreter and can become the direct perceiver when the physical sense base is silent. In jhāna, the mind does not need the physical eye to generate visual experience. The field of "seeing" persists, but it is now luminous, internal, and light.

Infinite Space and the Luminous Field

In MN 121 – Cūlasuññata Sutta, one progresses through refined perceptions:

Not attending to perceptions of the village, forest, or people… he attends to the perception of infinite space… of consciousness…

DN2

These perceptions are vast and often visual in a non-physical sense. They emerge not from external contact, but from purified saññā (perception) within the mind-only domain.

Think of jhānic vision like lucid dreaming: you see clearly, move, and even hear, but none of it comes through the physical body. It is not fantasy or delusion, but a luminous mental construct. Jhāna is far deeper than dreaming, but the mode of perception is mind-based.

So, your experience of "seeing" in jhāna without the heaviness of the senses is precisely what the early texts describe. The five senses go silent. Perception shifts to a luminous, internal basis, and the mind-made body becomes the new interface for reality.

Jhāna is not darkness or trance. It is luminous abiding, refined perception, and full awareness, a profound reorientation from external contact to internal clarity.

Right Concentration: Recreating the Mind-Made Body

As we progress in the gradual training, culminating in the mastery of jhāna, the purification of perception, and insight into the non-self nature of the aggregates, their relationship with the physical body (rūpakāya) begins to shift. This change is not simply symbolic but is an actual loosening of identification, support, and dependence on the material form.

The Tathagata described the emergence of a mind-made body (manomaya kāya) in many places, particularly in DN 2, the Sāmaññaphala Sutta, where he outlines the spiritual fruits of a recluse:

With his mind thus concentrated, purified, and bright… he produces from this body another body, having form, mind-made, complete in all its limbs and parts, not lacking any faculties.

DN2

This body is not bound by physical limitations but is a luminous, volitional construct entirely rooted in perception.

Letting go of the physical body does not mean ceasing awareness of it, but instead disentangling perception and identity from its structures. This is cultivated through:

Clarity in perception (saññā): When abiding in jhāna, perception can be refined to such an extent that the gross elements fade.

Mastery over form (rūpa-saññā): We no longer perceive through the physical body's boundaries but through the luminous mental body.

At this stage, recreating the body means intentionally generating the perception of a body from within the mind: each limb, each faculty, like an artist reconstructing a sculpture, not from clay but from perception itself.

He makes a mind-made body complete in all its parts, not deficient in any faculty…

DN2

This means: perception reproduces function: seeing, hearing, speaking, all recreated in this luminous form.

The mind-made body is not metaphysical speculation, it has pragmatic use in advanced practice:

-

Maintaining Interaction: As attachment to the physical body fades, the mind-made body allows interaction with perception-based experiences and others.

-

Refined Investigation: It becomes a vehicle for insight, examining the aggregates without being hindered by gross sensations.

-

Stability in Formless Realms: Even when bodily perception ceases (e.g., arūpa-jhāna), a subtle internal "form" (perceived through perception) helps maintain continuity of awareness.

We should not cling even to the mind-made body. As refined as it is, it remains constructed and impermanent. The culmination of wisdom is the abandonment of even this luminous body:

There comes a time, disciples, when the mind-made body is also seen as impermanent, constructed, not-self...

DN2

While not explicit stated in the Suttas, these instructions align with the spirit of suttas:

Stage 1: In the 4th jhāna, let the body perception become transparent.

Stage 2: Reconstruct each part with perception: limbs, organs, faculties, "seeing" them as made of light or clarity.

Stage 3: Observe the body acting, moving, speaking, all without physical basis. Let perception operate as intention without resistance.

This is not imagination or fantasy, it is grounded, vivid, wakeful clarity operating in a subtler realm.

Remember that even the most luminous body is conditioned. The aim is to use it skillfully, but not to mistake it for a refuge.

The mind-made body is a tool, not a destination. It supports deep liberation work when physical constraints fall away. But liberation lies beyond any body, material or mental.

Right Concentration: The Luminous Mind

The Tathagata describes progressively more luminous and refined states of mind and form, especially in connection with meditative absorption and the transcendence of ordinary perception. The teachings suggest that these luminous states are both experiential milestones and insight supports, though not ends in themselves.

Let us explore two important themes:

- Luminous Mind (Pabhassara Citta)

Luminous, disciples, is the mind. And it is defiled by incoming defilements.Luminous, disciples, is the mind. And it is freed from incoming defilements.

AN1.51

This "luminous mind" is the unclouded, pure consciousness that becomes accessible in deep stillness, especially in the fourth jhāna. It is not the unconditioned (nibbāna), but it is a powerful basis for seeing reality clearly.

When this mind is freed from the five hindrances, and especially in non-sensual perception, its luminosity becomes apparent.

- The Infinite Perception and Formless Attainments

As one cultivates jhāna and begins entering the arūpa samāpattis (formless attainments), the Tathagata describes states such as:

- Perception of infinite space

- Perception of infinite consciousness

- Perception of nothingness

- Neither-perception-nor-non-perception

In the Cūḷasuññata Sutta, the Buddha explicitly teaches how a monk goes beyond the perception of form:

Not attending to the perception of the village, the forest, of people, of wilderness… he directs the mind to the perception of infinite space… of infinite consciousness… of nothingness… of neither perception nor non-perception.

MN121

These are more luminous not because of light in a literal sense, but because they are free from coarseness, agitation, and duality. They are subtle, expansive, and tranquil, allowing the mind to become utterly pliable and powerful.

- The Radiance of Brahma and the "Body Made of Mind"

In DN 11 – Kevaṭṭa Sutta, the Tathagata describes a being arising in the Brahma world who perceives themselves as:

I am Brahmā, the Great Brahmā, the Conqueror, Unconquered… having created this cosmos… these beings are my creation.

DN11

This luminous Brahmā form is still a product of perception and karma, and the Tathagata reveals that even these highly luminous beings are still within samsāra, still impermanent, still not-self.

Reconstructing the mind-made body, is a gateway to these luminous and refined states, but they should be seen as means, not ends.

Even blissful, radiant, vast states, if clung to, become obstructions. But used wisely, they allow the mind to observe impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and not-self with extraordinary clarity.

Right Concentration: From Luminosity to Insight

While the luminous experience of jhāna and the mind-made body offers profound joy, stability, and clarity, the Tathagata's teaching does not stop there. Jhāna is a tool, not a destination. The true purpose of cultivating such a refined state is to turn it toward wisdom.

We will now explore how we can move from luminous abiding to insight into impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and non-self.

Jhāna as a Basis for Insight

The mind-made body and purified mind in jhāna provide the ideal platform for seeing deeply.

In MN 111, Anupada Sutta, Sāriputta, dwelling in jhāna, investigates each experience:

He discerned: 'This is the first jhāna... this is its arising... this is its passing away... this is its gratification... danger... and escape.'

MN111

This is the essence of practice: to observe the conditioned nature of even the most refined states, and see that they too are not self.

-

Impermanence (Anicca): Even the mind-made body arises and passes away. Its clarity is not eternal.

-

Suffering (Dukkha): Clinging to even luminous peace results in subtle dissatisfaction, as change inevitably comes.

-

Not-self (Anattā): These refined forms and perceptions are dependently arisen. They cannot be owned or controlled.

Disenchantment (Nibbida): The Turning Point

As the luminous states are seen as conditioned and not-self, the mind no longer clings. This moment of disenchantment (nibbida) is the beginning of true freedom. As described in SN 12.23:

From contact comes feeling; from feeling, craving... but when there is dispassion, there is release.

SN12.23

We now cease to construct, even subtly. The luminous body is let go, and attention turns toward the unconditioned.

Cessation: What Remains When We Let Go

The culmination of insight is not more refined perception, but the ending of perception and feeling altogether.

When one does not regard form, feeling, perception, formations, and consciousness as self... one is liberated through non-clinging.

MN64

This is Nibbāna, the cessation of fabrication, where nothing needs to be perceived or constructed.

The luminous mind-made body is not the final goal. It is a purified ground from which wisdom can clearly discern the nature of phenomena. Through seeing the conditioned as conditioned, and letting go of even the subtlest clinging, the mind turns away from birth and death and toward the deathless.

Thus, right concentration flows into right wisdom, and wisdom into release.

From Hijacking to Purification: Training the Mind in Right Concentration

In ordinary experience, the mind is untrained. It continuously hijacks raw sensory data and overlays it with distorted perceptions, views, emotions, and self-centered fabrications. The Tathagata described this in many discourses, how perception, when rooted in craving and ignorance, becomes the basis for delusion and suffering.

But through the Noble Eightfold Path, and specifically through the development of right concentration, this very same mind becomes the ground for liberation.

Let's explore how jhāna transforms the mind from a hijacker of awareness into a vehicle of purification, by refining:

Intention (how we relate to experience), Attention (what we attend to), and Perception (how we construct our experience).

Hijacking Awareness Through Deluded Perception

The untrained mind interprets reality through the six senses, sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, and mind, and then projects personal meaning onto those impressions. As explained in the Mālukyaputta Sutta:

Dependent on the eye and forms, eye-consciousness arises... With contact as condition, feeling; with feeling, craving; with craving, perception; with perception, mental proliferation...

SN35.232

Here, perception becomes distorted by craving and self-view, producing mental agitation and suffering.

Fabricating Wholesome Perceptions

In right concentration, we don’t eliminate fabrication. Instead, we purify it. As the Tathagata taught, perception and feeling are mental fabrications that can be cultivated intentionally:

What is mental fabrication? Perception and feeling.

MN44

We begin to replace coarse perceptions with refined, wholesome ones:

The breath, The four elements (earth, water, fire, air), Loving-kindness, Light, Space, Stillness.

These are not random images, but deliberate training perceptions that cleanse the mind of defilement and unify it in samādhi.

Dwelling in Wholesome, Mental Perception

In the first four jhānas, the Tathagata described how the mind gradually becomes unified, blissful, and equanimous, sustained entirely by internal perception.

We no longer perceive the gross body.

One who has entered upon the first jhāna does not see forms with the eye, or hear sounds with the ear.

MN140

Instead, one experiences the mental body (manomaya kāya), described in DN 9 – Poṭṭhapāda Sutta:

Another body is fabricated, mental, complete in all its parts, not deficient in any faculty.

DN9

This body is not composed of the four elements but of refined, fabricated perception, experienced internally.

Refining Perception through Elemental and Emptiness Meditation

As one cultivates jhāna, perception becomes increasingly purified. One powerful method is the Four Elements practice, taught in the Mahārāhulovāda Sutta:

Develop practice on the elements: ‘Earth element, water element, fire element, air element.’ ... This overcomes the perception of the body as self.

MN62

Later, even elemental perception can be transcended. In the Cūḷasuññata Sutta, the Tathagata describes how a practitioner moves beyond perceptions of form, place, space, and even consciousness, entering the vastness of emptiness:

Not attending to perceptions of the village, or of people, he attends to the perception of wilderness... He goes beyond that too.

MN121

Each stage purifies perception further until only the subtlest awareness remains , and even that can be let go.

From Fabricated to Unfabricated: Toward Liberation

Even the purest jhānic perception is still fabricated , still conditioned. But it becomes the launchpad for insight. In the Āneñjasappāya Sutta, the Tathagata instructs:

This perception is peaceful, sublime, but still fabricated... Not clinging to it, his mind is liberated.

MN106

The Disciple sees: “All of this , breath, light, form, even vast space , is not me, not mine.” This insight leads to non-clinging, and ultimately to cessation (nirodha).

Right Concentration as Purification

Instead of the mind hijacking awareness with its old habits of delusion, we now train the mind to:

Purify intention, letting go of sensuality, ill-will, and delusion. Purify attention, sustaining focus on wholesome, unified objects. Purify perception, progressively refining what we experience and how.

This is not suppression, but liberation through purification, not escaping the world, but seeing it clearly by seeing through it.

Friend Visakha, concentration is the unification of the mind; the four foundations of mindfulness are the signs of concentration; the four right efforts are the requisites for concentration. The frequent practice and cultivation of these very states is the development of concentration.

MN44

Visakha further asks, but what is concentration, and what are the things that are the foundations of concentration, the prerequisites of concentration, and what is the development of concentration? Bhikkhuni Damadina answers, Unification of mind is concentration. The four kinds of mindfulness meditation are the foundations of concentration. The four right efforts are the prerequisites for concentration, and the cultivation, development, and making much of these very same things is the development of concentration.

MN44

There are, Ananda, eight liberations. What are the eight?

One perceives form internally, and external forms are seen. This is the first liberation.

Perceiving internally the mind is formless, external forms are seen. This is the second liberation.

Being intent only on beauty. This is the third liberation.

Completely transcending the perception of form, with the disappearance of the perception of resistance, not attending to the perception of diversity, thinking Infinite space, one enters and dwells in the base of infinite space. This is the fourth liberation.

Completely transcending the base of infinite space, thinking Infinite consciousness, one enters and dwells in the base of infinite consciousness. This is the fifth liberation.

Completely transcending the base of infinite consciousness, thinking There is nothing, one enters and dwells in the base of nothingness. This is the sixth liberation.

Completely transcending the base of nothingness, one enters and dwells in the base of neither-perception-nor-non-perception. This is the seventh liberation.

Completely transcending the base of neither-perception-nor-non-perception, one enters and dwells in the cessation of perception and feeling. This is the eighth liberation.

These, Ananda, are the eight liberations. When a disciple, Ananda, can enter and emerge from these eight liberations in forward and reverse order, as he wishes, having witnessed them for himself through direct knowing in this very life, and having attained to the mental and wisdom liberation, he is called a disciple who is liberated in both respects.

And this, Ananda, is called the liberation in both respects, beyond which there is none other.

There is no liberation superior or more excellent than this. Thus spoke the Blessed One. The venerable Ānanda was delighted with what the Blessed One had said.

DN15

And what is the development of concentration that, when developed and cultivated, leads to the destruction of the taints? Here a disciple dwells contemplating the rise and fall in the five aggregates of clinging: Such is form, such is the arising of form, such is the passing away of form; such is feeling, such is the arising of feeling, such is the passing away of feeling; such is perception, such is the arising of perception, such is the passing away of perception; such are formations, such is the arising of formations, such is the passing away of formations; such is consciousness, such is the arising of consciousness, such is the passing away of consciousness. This is the development of concentration that, when developed and cultivated, leads to the destruction of the taints.

AN4.41

The mind is stable, settled, firm, not distracted, not disturbed; it has mental imperturbability, is calm, and possesses the spiritual faculty of concentration, the power of concentration, Right Concentration.

Understanding Jhāna

Read the following sutta to understand how Jhāna is the natural result when one practices the Tathagata's gradual training:

The Experience of Real Jhāna

Anyone with practical experience knows that when you sit in a meditation room after communicating with someone, chatting, dialogues, discussions, and disputes with this person will continue to appear in your mind, which is difficult to calm down for a long time, making you very tired and difficult to enter meditation , I often think, this annoying words are always lingering, what is the reason?

Once I found out that it was because I kept thinking of a certain person in my mind. When a certain person's image appeared, I had a conversation with him. If I didn't think of a certain person in my mind, there would be no conversation with him. At this time, I was already in the quiet room, and no one would talk to me. Why should I keep thinking about someone, letting go of these endless conversations would only increase my fatigue? Therefore, when anyone’s image appear in my mind, I let it go, because when I let go of thinking about people, the dialogue with people in my mind disappears, and my heart is purified.

After so much practice, I found that even if no anyone else’s image appear in my mind, there will still be words in my mind, which is not pure enough. What is the reason? I realized that although no specific person image appears, there are still talking in the mind. Because of the habitual thinking of others and me, when there is a known phenomenon, I habitually translate it into language, but now I don’t need to describe what I know to anyone, why don't I give up all words and just live in solitary knowing? As if there is no one in the world but me, all the words in my mind will stop at this moment, and my heart will be silent.

After so much practice, I found that when the words are silent, knowledge begins to appear in the form of vision, for example, when I hear a bird singing, I see the bird image, but I have not actually seen the bird. How did such a image arise? I realized that “there are birds” is just a perception, no matter whether there are birds singing or not, this perciption is definitely not real, such an unreal perrception, why should I care about it? When I found out that everything I know is like this, I no longer pay attention to all perceptions, and just live in the truthful kowing without perceptions.

After being stabilized in this way, I found that when I hear the sound, the only real knowledge is the hearing consciousness. Once there is such hearing counsciousness, there are following sound perception and ear perception. When there is no such hearing counsciousness, there is no arise of consequent thinking about the sound you heard. If there is a sound. Thinking, ear thinking, it thinking, I thinking, thinking here, thinking there, thinking inside, thinking outside, if there is no such hearing consciousness, these thoughts will not arise. Consciousness is the origin of all these . It is further discovered that all external knowledge is like this. When a corresponding consciousness arises, there will be a corresponding thought.

However, before the consciousness arises, there is no place to come from, and after it disappears, there is no other place to exist. It arises and perishes due to conditions. , Self-generated and self-destroyed, has nothing to do with me, and the corresponding thoughts after the consciousness arises are born because of the consciousness, and have nothing to do with me, why should I care about them? When I am determined in this way, I will no longer pay attention to all external knowledge, nor will I have any external thoughts. When I don’t think about external things or think externally, external consciousness will no longer arise.

In this way, I discovered that when I know that there is a sound, it has leaks and actions. When I know that there are ears, this also has leaks and actions. There will be no birth, the heart will be still, without leaks, and will not act. This is like a lighted candle in a room. When there is an air leak, the flame will move, and when there is no air leak, the flame will remain still. It is also like a person standing in a bush of thorns. When he moves, he will feel pain. Because of the pain, he will know that there is a thorn. If he does not move, he will not feel pain, and he will not know that there is a thorn.

After practicing so much, I found that in such a state, there are still perceptions and volitional formations. To have thoughts is to do something and to be reborn. If life ends at this time, nothing will disappear. It’s just that these thoughts don’t arise, and there’s nothing to be afraid of; if life continues, there is nothing continuing, just the rebirth of these thoughts, there is rebirth, there is feeling, and there is suffering, when I see the harmlessness of thoughts that are not born and the danger of rebirth. At this time, the mind tends to do nothing and abandons all thinking and volitional formations.

The above experiences arose naturally in the process of my continuous meditation practice. This process spanned about two years. There are so many experiences that it is difficult to summarize systematically, so I only list some that I think have played an important role.

Here a disciple, secluded from sensual pleasures, secluded from unwholesome states, enters and dwells in the first jhāna, which is accompanied by thought and examination, with joy and pleasure born of seclusion.

He reflects thus: This first jhāna is fabricated and volitionally formed. But whatever is fabricated and volitionally formed is impermanent and subject to cessation.

Remaining thus, he attains the destruction of the taints.

MN52

MN52: In the Aṭṭhakanāgara Sutta, the householder Dasama from Aṭṭhakanagara seeks out Venerable Ānanda in Vesālī to learn about a single Dhamma taught by the Tathagata that can liberate an unliberated mind and destroy taints. Ānanda explains that through practices like entering various jhānas and developing boundless loving-kindness, compassion, joy, and equanimity, a disciple can achieve liberation or reach higher realms. Dasama, inspired by the teachings, honors Ānanda and supports the monastic community, expressing gratitude for discovering multiple paths to enlightenment.

Moggallāna, Moggallāna, do not be negligent regarding noble silence. Steady your mind in noble silence, unify your mind in noble silence, concentrate your mind in noble silence.

So, friends, later on, with the subsiding of thought and examination, I entered and dwelt in the second jhāna, which has internal confidence and unification of mind, is without thought and examination, and has rapture and happiness born of concentration.

SN21.1

SN21.1: The Kolita Sutta recounts an experience of Venerable Mahāmoggallāna at Sāvatthī in Jeta’s Grove. Mahāmoggallāna, in seclusion, pondered the meaning of "noble silence," realizing it referred to the state of the second jhāna—characterized by internal confidence, unification of mind, absence of thought, and joy from concentration. Despite initial distractions, he achieved this state following the Tathagata's advice to focus and stabilize his mind in noble silence. This attainment exemplified profound spiritual knowledge assisted by the Tathagata.

The Balanced Way

In practicing the Dhamma, if you don’t foster a balance between concentration and discernment, you’ll end up going wild in your thinking. If there’s too much work at discernment, you’ll go wild in your thinking. If there’s too much concentration, it just stays still and undisturbed without coming to any knowledge either. So you have to keep them in balance. Stillness has to be paired with discernment. Don’t let there be too much of one or the other. Try to get them just right. That’s when you’ll be able to see things clearly all the way through. Otherwise, you’ll stay as deluded as ever. You may want to gain discernment into too many things—and as a result, your thinking goes wild. The mind goes out of control. Some people keep wondering why discernment never arises in their practice, but when it does arise they really go off on a tangent. Their thinking goes wild, all out of bounds.

So when you practice, you have to observe in your meditation how you can make the mind still. Once it does grow still, it tends to get stuck there. Or it may grow empty, without any knowledge of anything: quiet, disengaged, at ease for a while, but without any discernment to accompany it. But if you can get discernment to accompany your concentration, that’s when you’ll really benefit. You’ll see things all the way through and be able to let them go. If you’re too heavy on the side of either discernment or stillness, you can’t let go. The mind may come to know this or that, but it latches onto its knowledge. Then it knows still other things and latches onto them, too. Or else it simply stays perfectly quiet and latches onto that.

It’s not easy to keep your practice on the Middle Way. If you don’t use your powers of observation, it’s especially hard. The mind will keep falling for things, sometimes right, sometimes wrong, because it doesn’t observe what’s going on. This isn’t the path to letting go. It’s a path that’s stuck, caught up on things. If you don’t know what it’s stuck and caught up on, you’ll remain foolish and deluded. So you have to make an effort at focused contemplation until you see clearly into inconstancy, stress, and not-self. This without a doubt is what will stop every moment of suffering and stress.…

A Glob of Tar

An important but subtle point is that even though we practice, we continue to fall for pleasant feelings, because feelings are illusory on many levels. We don’t realize that they’re changeable and unreliable. Instead of offering pleasure, they offer us nothing but stress—yet we’re still addicted to them.

This business of feeling is thus a very subtle matter. Please try to contemplate it carefully—this business of latching onto feelings of pleasure, pain, or equanimity. You have to contemplate so as to see it clearly. And you have to experiment more than you may want to with pain. When there are feelings of physical pain or mental distress, the mind will struggle because it doesn’t like pain. But when pain turns to pleasure, the mind likes it and is content with it, so it keeps on playing with feeling, even though as we’ve already said, feeling is inconstant, stressful, and not really ours. But the mind doesn’t see this. All it sees are feelings of pleasure, and it wants them.

Try looking into how feeling gives rise to craving. It’s because we want pleasant feeling that craving whispers—whispers right there at the feeling. If you observe carefully, you’ll see that this is very important, for this is where the paths and fruitions leading to nibbāna are attained, right here at feeling and craving. If we can extinguish the craving in feeling, that’s nibbāna.…

In the Soḷasa Pañhā (Sutta Nipāta 5), the Buddha said that defilement is like a wide and deep flood, but he then went on to summarize the practice to cross it simply as abandoning craving in every action. Now, right here at feeling is where we can practice to abandon craving, for the way we relish the flavor of feeling has many ramifications. This is where many of us get deceived, because we don’t see feeling as inconstant. We want it to be constant. We want pleasant feelings to be constant. As for pain, we don’t want it to be constant, but no matter how much we try to push it away, we still latch onto it.

This is why we have to pay attention to feeling, so that we can abandon craving right there in the feeling. If you don’t pay attention here, the other paths you may follow will simply proliferate. So bring the practice close to home. When the mind changes, or when it gains a sense of stillness or calm that would rank as a feeling of pleasure or equanimity: Try to see in what ways the pleasure or equanimity is inconstant, that it’s not you or yours. When you can do this, you’ll stop relishing that particular feeling. You can stop right there, right where the mind relishes the flavor of feeling and gives rise to craving. This is why the mind has to be fully aware of itself—all around, at all times—in its single-minded contemplation to see feeling as empty of self.…

This business of liking and disliking feelings is a disease hard to detect, because our intoxication with feelings is so very strong. Even with the sensations of peace and emptiness in the mind, we’re still infatuated with feeling. Feelings on the crude level—the violent and stressful ones that come with defilement—are easy to detect. But when the mind grows still—steady, cool, bright, and so on—we’re still addicted to feeling. We want these feelings of pleasure or equanimity. We enjoy them. Even on the level of firm concentration or meditative absorption, there’s attachment to the feeling.…

This is the subtle magnetic pull of craving, which paints and plasters things over. This painting and plastering is hard to detect, because craving is always whispering inside us, “I want nothing but pleasant feelings.” This is very important, for this virus of craving is what makes us continue to be reborn.…

So explore to see how craving paints and plasters things, how it causes desires to form—the desires to get this or take that—and what sort of flavor it has that makes you so addicted to it, that makes it hard for you to pull away. You have to contemplate to see how craving fastens the mind so firmly to feelings that you never weary of sensuality or of pleasant feelings no matter what the level. If you don’t contemplate so as to see clearly that the mind is stuck right here at feeling and craving, it will keep you from gaining release.…

We’re stuck on feeling like a monkey stuck in a tar trap. They take a glob of tar and put it where a monkey will get its hand stuck in it and, in trying to pull free, the monkey gets its other hand, both feet, and finally its mouth stuck, too. Consider this: Whatever we do, we end up stuck right here at feeling and craving. We can’t separate them out. We can’t wash them off. If we don’t grow weary of craving, we’re like the monkey stuck in the glob of tar, getting ourselves more and more trapped all the time. So if we’re intent on freeing ourselves in the footsteps of the arahants, we have to pay attention specifically on feeling until we can succeed at freeing ourselves from it. Even with painful feelings, we have to practice—for if we’re afraid of pain and always try to change it to pleasure, we’ll end up even more ignorant than before.

This is why we have to be brave in experimenting with pain—both physical pain and mental distress. When it arises in full measure, like a house afire, can we let go of it? We have to know both sides of feeling. When it’s hot and burning, how can we deal with it? When it’s cool and refreshing, how can we see through it? We have to make an effort to pay attention to both sides, contemplating until we know how to let go. Otherwise we won’t know anything, for all we want is the cool side, the cooler the better…and when this is the case, how can we expect to gain release from the cycle of rebirth?

Nibbāna is the extinguishing of craving, and yet we like to stay with craving—so how can we expect to get anywhere at all? We’ll stay right here in the world, right here with stress and suffering, for craving is a sticky sap. If there’s no craving, there’s nothing: no stress, no rebirth. But we have to watch out for it. It’s a sticky sap, a glob of tar, a dye that’s hard to wash out.

So don’t let yourself get carried away with feeling. The crucial part of the practice lies here.…

Discussion on Concentration

In the Middle Length Discourses (Majjhima Nikaya), the Buddha recounted his experiences from the time he renounced the householder's life. He described how he achieved the seventh and eighth levels of concentration known as the "Jhāna of Nothingness" and the "Jhāna of Neither Perception nor Non-Perception," respectively, under two well known teachers of the time.

MN36: In a less confrontational meeting, the Tathagata and Saccaka discuss the difference between physical and mental development. The Tathagata gives a long account of the various practices he did before awakening, detailing the astonishing lengths he took to mortify the body.

In the Middle Length Discourses (Majjhima Nikaya 36), the Buddha also described his experience of practicing meditation under the shade of the cool, sal tree while his father was involved in Sakyan affairs. During this meditation, the Buddha achieved the first Jhāna, which involved experiencing "piti" (rapture) and "sukha" (pleasure) and seclusion from sensory desires.

MN26: This is one of the most important biographical discourses, telling the Tathagata’s experiences from leaving home to realizing awakening. Throughout, he was driven by the imperative to fully escape from rebirth and suffering.

In the same Middle Length Discourses (Majjhima Nikaya 26), the Buddha mentioned that he had no teacher in this world, implying that he realized the truth by himself. This indicates that the meditation he practiced before and after attaining enlightenment was different because if it were the same, he would have merely surpassed his teachers and would not have claimed that he had no teacher. This suggests that there are two types of meditation, one is an external meditation, and the other is the meditation that the Buddha realized himself.

In the Theravada tradition, two major forms of meditation are recognized: Samatha (calming) meditation and Vipassana (insight) meditation. Both of these have different meditation objects and techniques. Samatha meditation focuses on calming the mind by concentrating on a single object, while Vipassana meditation involves contemplating the impermanence and insubstantiality of phenomena. These two forms of meditation share common factors in the early stages, but they diverge in their emphasis and purpose.

The difference between these two types of meditation is that Samatha meditation uses a fixed object as its focus, leading to tranquility, while Vipassana meditation employs the ever-changing sensory experiences as its object to reach momentary concentration. Many believe that Vipassana meditation is the meditation that the Buddha himself realized.

However, early texts in the Pali Canon and the early Buddhist Abhidhamma tradition describe a different type of meditation. This meditation involves renouncing sensual desires, unwholesome mental qualities, and cultivating right mindfulness and right understanding. This form of meditation is often referred to as authentic meditation.

In this authentic meditation, the practitioner does not rely on any specific object. Instead, the focus is on renunciation, right mindfulness, and right understanding. This is the only meditation that the Buddha explicitly taught.

To practice this authentic meditation, one doesn't rely on a specific target; it's all about renouncing and dwelling in renunciation. In sharp contrast to Samatha and Vipassana meditation, this authentic meditation doesn't require concentration on an external object.

It's essential to remember that this practice is not dependent on any object. It leads towards renunciation and staying in renunciation. This is the unique meditation taught by the Buddha in the early texts.

In conclusion, it appears that the Buddha indeed realized a new form of meditation, which allowed him to attain enlightenment. He continued to teach this meditation throughout his life. However, soon after the Buddha's parinirvana, the true meaning of this meditation began to be confused with external meditation practices, misinterpreted, and altered. The presence of these alterations is evident in the earliest versions of the scriptures, indicating that the period of the true Dharma's preservation was indeed quite brief.

This is a brief discussion on these theoretical aspects of meditation. For those interested in a more detailed understanding, you may refer to my 14th and 15th essays on my meditation experiences, which could provide further insight into this authentic meditation.

AN4.41: The Aṅguttara Nikāya 4.415 outlines four types of concentration development: 1) Concentration leading to a pleasant abiding in the present, achieved through seclusion from sensual pleasures and entering the fourth jhāna. 2) Concentration leading to knowledge and vision, cultivated by focusing on the perception of light and maintaining a bright, unclouded mind. 3) Concentration leading to mindfulness and clear comprehension, developed by being aware of the arising and passing of feelings, perceptions, and thoughts. 4) Concentration leading to the destruction of taints, achieved by contemplating the rise and fall of the five aggregates subject to clinging. These teachings aim to guide disciples towards peace and liberation from birth and aging.

The Uses of Equanimity

The sensations of the mind are subtle and very volatile. Sometimes passion or irritation can arise completely independent of sensory contact, simply in line with the force of one’s character. For instance, there are times when the mind is perfectly normal, and all of a sudden there’s irritation—or the desire to form thoughts and get engrossed in feelings of pain, pleasure, or equanimity. We have to contemplate these three kinds of feeling to see that they’re inconstant and always changing, and to see that they are all stressful, so that the mind won’t go and get engrossed in them. This business of getting engrossed is very subtle and hard to detect. It keeps us from knowing what’s what because it’s delusion pure and simple. Being engrossed in feelings of pleasure is something relatively easy to detect, but being engrossed in feelings of equanimity: That’s hard to notice, because the mind is at equanimity in an oblivious way. This oblivious equanimity keeps us from seeing anything clearly.

So you have to focus on seeing feelings simply as feelings and pull the mind out of its state of being engrossed with equanimity. When there’s a feeling of equanimity as the mind gathers and settles down, when it’s not scattered around, use that feeling of equanimity in concentration as the basis for probing in to see inconstancy, stress, and not-self—for this equanimity in concentration at the fourth level of absorption (jhāna) is the basis for liberating insight. Simply make sure that you don’t get attached to the absorption.

If you get the mind to grow still in equanimity without focusing on gaining insight, it’s simply a temporary state of concentration. So you have to focus on gaining clear insight either into inconstancy, into stress, or into not-selfness. That’s when you’ll be able to uproot your attachments. If the mind gets into a state of oblivious equanimity, it’s still carrying fuel inside it. Then as soon as there’s sensory contact, it flares up into attachment. So we have to follow the principles the Buddha laid down: Focus the mind into a state of absorption and then focus on gaining clear insight into the three characteristics. The proper way to practice is not to let yourself get stuck on this level or that—and no matter what insights you may gain, don’t go thinking that you’ve gained Awakening. Keep looking. Keep focusing in to see if there are any further changes in the mind and, when there are, see the stress in those changes, the not-selfness of those changes. If you can know in this way, the mind will rise above feeling, no longer entangled in this level or that level—all of which are simply matters of speculation.

The important thing is that you try to see clearly. Even when the mind is concocting all sorts of objects in a real turmoil, focus on seeing all of its objects as illusory. Then stay still to watch their disbanding. Get so that it’s clear to you that there’s really nothing to them. They all disband. All that remains is the empty mind—the mind maintaining its balance in stability—and then focus in on examining that.

There are many levels to this process of examining the diseases in the mind, not just one. Even though you may come up with genuine insights every now and then, don’t just stop there—and don’t get excited about the fact that you’ve come to see things you never saw before. Just keep contemplating the theme of inconstancy in everything, without latching on, and then you’ll come to even more penetrating insights.…

So focus on in until the mind stops, until it reaches the stage of absorption called purity of mindfulness and equanimity. See what pure mindfulness is like. As for the feeling of equanimity, that’s an affair of concentration. It’s what the mindfulness depends on so that it too can reach equanimity. This is the stage where we gather the strength of our awareness in order to come in and know the mind. Get the mind centered, at equanimity, and then probe in to contemplate. That’s when you’ll be able to see.…

But, Ānanda, this dwelling has been fully awakened to by the Tathāgata, which is: non-attention to all signs, dwelling internally in emptiness...

Therefore, Ānanda, if a disciple wishes: May I dwell internally in emptiness, then, Ānanda, that disciple should steady, settle, unify, and concentrate his mind internally.

And how, Ānanda, does a disciple steady, settle, unify, and concentrate his mind internally? Here, Ānanda, a disciple, secluded from sensual pleasures, secluded from unwholesome states, enters and dwells in the first jhāna... the second jhāna... the third jhāna... the fourth jhāna.

Thus, Ānanda, a disciple steadies, settles, unifies, and concentrates his mind internally. He makes emptiness his object of meditation. For one making emptiness his object of meditation, the mind does not launch out, does not become placid, does not settle, does not become liberated.

Thus, Ānanda, a disciple knows: While I make emptiness my object of meditation, the mind does not launch out, does not become placid, does not settle, does not become liberated. Thus he is fully aware there. He makes emptiness his object of meditation externally... He makes emptiness his object of meditation both internally and externally... He makes signlessness his object of meditation.

MN122

First I say that depending on the first jhāna, the destruction of the taints occurs, thus it has been said. Why was this said?

Here a disciple, having secluded himself from sensual pleasures... enters and dwells in the first jhāna.

Whatever there is in that state of form, feeling, perception, formations, and consciousness, he sees those phenomena as impermanent, suffering, a disease, a boil, a dart, a calamity, an affliction, alien, disintegrating, empty, not-self.

He turns his mind away from those phenomena.

Having turned his mind away from those phenomena, he directs his mind towards the deathless element: This is peaceful, this is sublime, that is, the stilling of all formations, the relinquishing of all attachments, the destruction of craving, dispassion, cessation, Nibbāna.

Standing upon that, he attains the destruction of the taints.

AN9.36

How many conditions, friend, are there for the attainment of the liberation of mind that is free from pleasure and pain? There are four conditions, friend, for the attainment of the liberation of mind that is free from pleasure and pain.

Here, friend, a disciple, having abandoned pleasure and pain, and with the previous disappearance of joy and grief, enters and remains in the fourth Jhāna, which is neither painful nor pleasant and includes the purification of mindfulness by equanimity. These are the four conditions for the attainment of the liberation of mind that is free from pleasure and pain.

How many conditions, friend, are there for the attainment of the signless liberation of mind? There are two conditions, friend, for the attainment of the signless liberation of mind: non-attention to all signs and attention to the signless element. These are the two conditions for the attainment of the signless liberation of mind.

How many conditions, friend, are there for the maintenance of the signless liberation of mind? There are three conditions, friend, for the maintenance of the signless liberation of mind: non-attention to all signs, attention to the signless element, and prior determination. These are the three conditions for the maintenance of the signless liberation of mind.

How many conditions, friend, are there for the emergence from the signless liberation of mind? There are two conditions, friend, for the emergence from the signless liberation of mind: attention to all signs and non-attention to the signless element. These are the two conditions for the emergence from the signless liberation of mind.

Are these liberations of mind: boundless liberation of mind, liberation of mind through nothingness, liberation of mind through voidness, and signless liberation of mind: different in both meaning and terminology, or are they the same in meaning and only different in terminology?

There is a way, friend, in which these liberations of mind are different in both meaning and terminology, and there is a way in which they are the same in meaning and only different in terminology. What is the way in which they are different in both meaning and terminology?

Here, friend, a disciple abides pervading one direction with a mind imbued with loving-kindness, likewise the second, likewise the third, likewise the fourth; so above, below, around, and everywhere, and to all as to himself, he abides pervading the all-encompassing world with a mind imbued with loving-kindness, abundant, exalted, immeasurable, without hostility, and without ill-will. This is called the boundless liberation of mind.

And what is the liberation of mind through nothingness? Here, friend, a disciple, by completely surmounting the base of infinite consciousness, aware that there is nothing, abides in the base of nothingness. This is called the liberation of mind through nothingness. And what is the liberation of mind through voidness? Here, friend, a disciple, by abiding in voidness...

Whether he is in the forest, at the foot of a tree, or in an empty hut, he reflects: This is empty of a self or what belongs to a self. This, friends, is called emptiness liberation of mind. And what, friends, is the signless liberation of mind? Here, friends, a disciple, not paying attention to any signs, dwells in the concentration of mind that is signless.